Angelenos and their neighbors rely on a complex network of reservoirs, canals, and pipelines that bring water from the wetter parts of northern California to the parched basins and valleys of the south.

Protecting any water distribution infrastructure from corrosion is essential to its performance. But the stakes are that much higher when the basic habitability of an entire region depends on manmade infrastructure for a reliable water supply.

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California’s (MWD) Etiwanda Pipeline is one piece of the region’s water puzzle. The 12-foot wide pipeline stretches 10 miles beneath the communities of Fontana and Rancho Cucamonga north of Los Angeles.

Inside the pipeline, a serious problem had emerged: The original cement mortar lining applied when the pipeline was first built in the 1990s had begun falling apart. And though the start of a rehab of the pipeline in autumn 2022 was welcome news, it took the pipeline out of service. Existing redundancies meant that water would still flow for customers, but relying on backups for primary supply is riskier the longer it persists.

MWD was clear that the work needed to be fast and efficient. And that was before it started raining.

Severe drought conditions led to mortar lining failure

The Etiwanda Pipeline’s original cement mortar lining was a perfectly adequate corrosion protection solution for its time.

But times have changed.

Mortar linings must remain damp for optimal performance, and for most water pipelines, that’s not a problem. But more frequent and more severe droughts across California left the Etiwanda Pipeline dry at times. In periods of no water, the mortar dried out and began to crack. When water again filled the pipeline, the force of its motion caused chunks of weakened mortar to break free.

The result: unimpeded corrosion of newly exposed steel.

During an initial phase of the rehab, MWD trialed various lining products from a host of manufacturers. Carboline’s Polyclad 767, a rigid polyurethane formula designed for water and wastewater pipeline and water tank lining applications, performed best and was specified for the remainder of the work. Its fast-cure properties would end up being critical to the project.

A firm 10-month timeline for the reline was agreed.

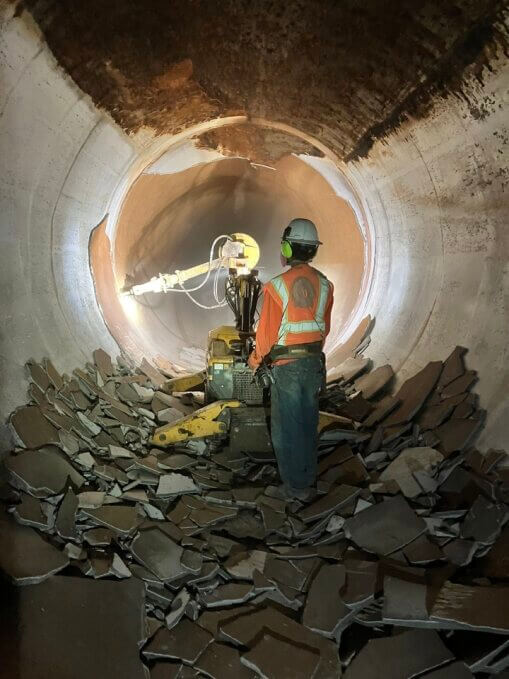

But before the new protective lining could go on, the old cement mortar needed to come off. This was as tedious as it was complex because the only way to remove it was by breaking it up into pieces small enough to lift out of manholes.

Crews from project contractor F.D. Thomas started by breaking the mortar off the pipeline with jackhammers and loading the waste into a motorized carrier. The carrier, which looks like a cross between a forklift and a tiny dump truck, would then make its way to the nearest manhole, where the mortar pieces were transferred to a conveyor and hoisted out of the pipeline piece by piece.

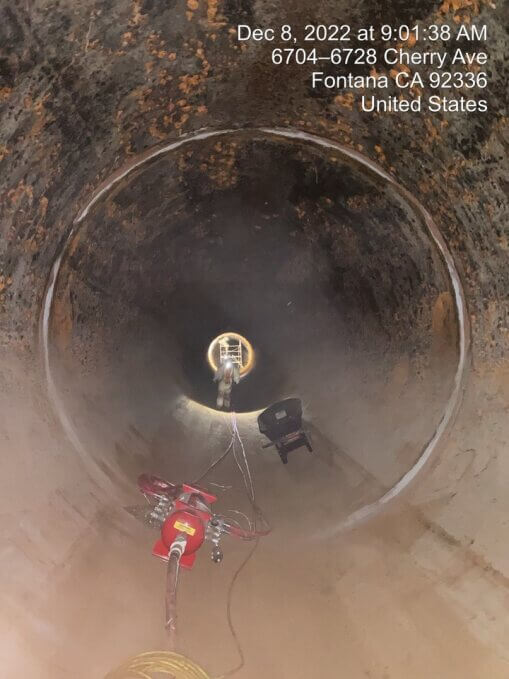

Surface preparation and lining application followed. Specialized rotary spray equipment would assure consistent application of the lining.

Crews moved methodically along the pipeline, manhole by manhole, mile by mile, 24 hours a day and five days a week.

The good and the bad of too much rain

The first months of 2023 were marked by atmospheric rivers that dumped intense rains across California and the western U.S. The storms brought with them severe floods and landslides, but they also erased what had been a deep drought.

With its reservoirs replenished, California authorities announced in the spring that water districts served by the State Water Project would be allocated 100% of the water they had asked for.

A 100% allocation is rare, so no water district in its right mind would turn it down. That included the MWD, even as its crucial Etiwanda Pipeline was out of service and would remain so for months.

The district had planned to return the Etiwanda Pipeline to service in October 2023, but in June they informed F.D. Thomas that they needed to press hard to finish as quickly as they could.

Now, spray crews were working nonstop seven days a week, knowing that the moment they finished, MWD would open the gates to more water than it had seen in years.

Polyclad 767 features prove critical to success

It’s challenging enough to staff up spray crews on short notice to deliver a project ahead of schedule. But adding to the challenge is that a crew must confront certain inherent limitations of the products they’re working with—limitations which can put a project’s desired schedule at odds with what’s possible on the ground.

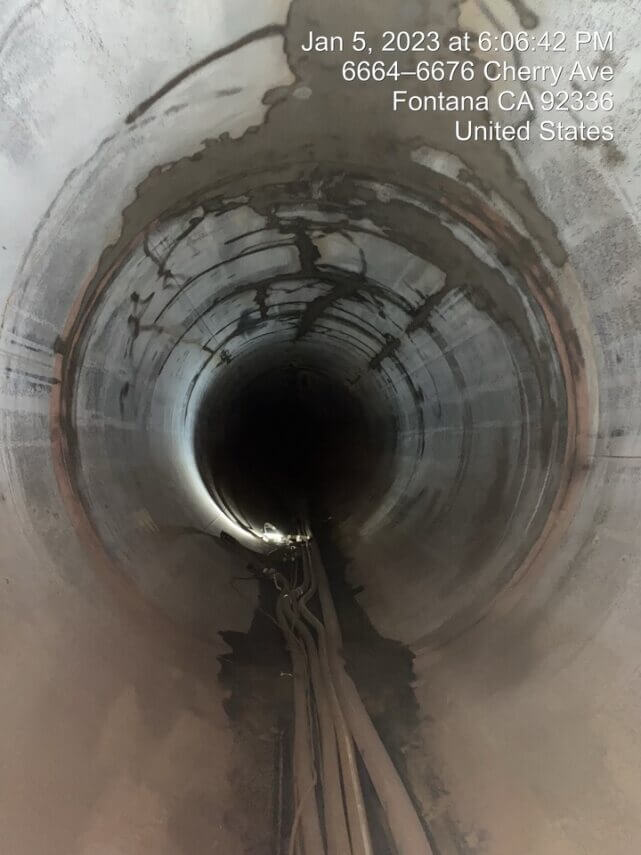

Or, under the ground in this instance, and the limitations were cure time and recoat window. For the new polyurethane lining to perform as intended, two coats were needed. Polyclad 767 ended up being the perfect choice because its cure time is short enough that the crew applying the second coat could safely guide the rotary spray equipment over the first coat after a very short wait, and its recoat window is long enough that the crew wouldn’t need to wipe down or abrade the first coat to ensure the second coat would adhere properly.

F.D. Thomas crews’ blitz—made possible partly due to the characteristics of Polyclad 767—paid off. Lining application wrapped up a staggering two months ahead of the initial schedule.

MWD placed the Etiwanda Pipeline back in service in August 2023, in time to receive the water that millions in this region needed so badly.