How do you judge whether a corrosion protection system is “good?”

Manufacturers pre-judge their products as good all the time.

But talk is cheap, and even a strong score from the lab will never be as convincing as field performance.

Here, we discuss two bridge coating projects where the same “ordinary” corrosion protection system was specified. And while in many ways the projects were similar, they couldn’t have been more different in terms of their context.

One of these bridges, you’ve probably never heard of. The other, nearly everyone has.

Photo courtesy of Famartin.

Photo courtesy of Famartin.

Point-No-Point Bridge, New Jersey

Even if locals around Newark or Hoboken do know about this plain steel swing-type railroad bridge crossing the Passaic River, they probably don’t know how it got such a strange name.

We don’t, either. We tried.

Owned by Conrail and serving CSX freight trains, Point-No-Point is one of many swing bridges common to this area. The Passaic is still navigable at this location 2.6 miles in from Newark Bay, so when barges need to pass, Point-No-Point swings open.

It’s worked this way since the bridge was built in 1901.

It could work better, though.

The distance between Point-No-Point’s piers restricts the size of vessels traveling past them. Bigger boats could go farther upriver if not for this limitation. Another limitation is the time it takes to open and close the bridge: Five hours each way. Scheduling freight trains would be much easier on CSX if a passing boat didn’t trigger a 10-hour outage of their tracks.

So at the end of 2022, a long-awaited replacement project began. The feet of the new swing bridge will stand wider apart, allowing bigger vessels to reach customers farther upriver. It will take just five minutes to open or close the span.

A marked improvement, but this is an ordinary modern swing bridge. Its design is familiar to anyone who’s seen a railroad overpass before, and it does what its predecessor did for over 120 years.

The three-coat zinc-epoxy-urethane system specified to protect the bridge’s steel is also familiar to anyone in the coatings industry.

Carbozinc 11 HS is an ultra-low VOC inorganic zinc primer with very high zinc loadings ideal for environments where salting is expected. Being a railroad bridge, road salt is not a concern, but the Passaic River at this location is brackish at times owing to tides.

Carboguard 893 is a high-solids epoxy commonly specified as an intermediate over zinc-rich primers and suitable beneath a wide range of urethane topcoats. It offers very good corrosion protection and meets current AIM VOC criteria.

Carbothane 133 LV is a high-solids, high-build urethane topcoat with exceptional weathering characteristics. In addition to strong performance, its low VOC and HAPs content are critical for specification in areas with stricter environmental regulations such as the northeast U.S.

These products together are considered a standard coating system, but do not interpret “standard” to mean “average.” Rather, this system has set the standard—and sets it again and again with incremental improvements toward higher solids and lower VOC content.

That’s why it’s so familiar. It’s worked so well for so long.

No mystery, then, why that same system was essential to the rapid reopening of one of the busiest stretches of highway in the country.

I-95 bridge replacement, Philadelphia

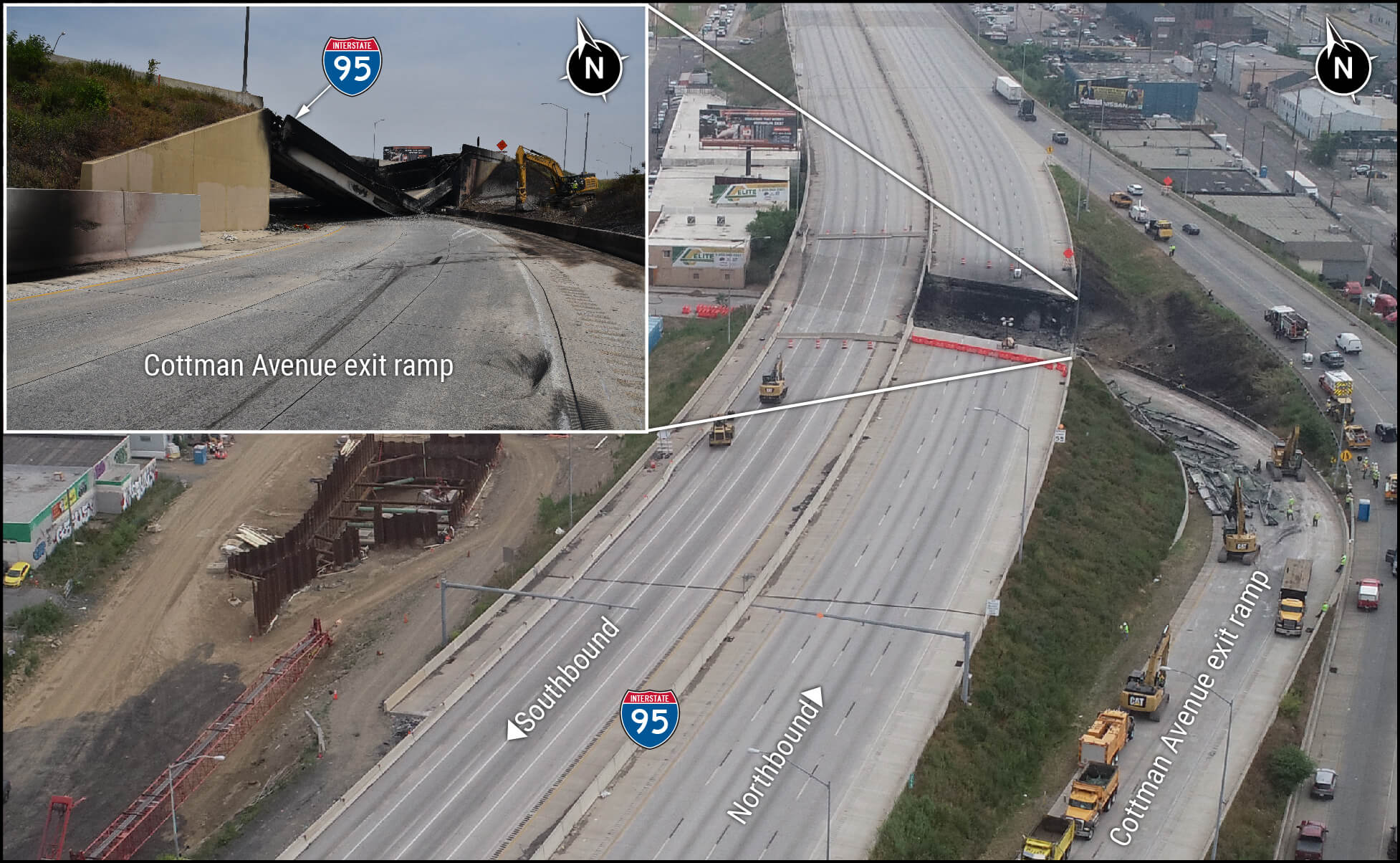

The bridge carrying I-95 over Cottman Avenue in northeast Philadelphia was as ordinary as overpasses get. But an extraordinary crash on the morning of June 11, 2023, brought the bridge down—and news cameras brought everyone the story.

A tanker truck laden with 8,500 gallons of gasoline lost control on the off-ramp, overturned, and exploded beneath the highway. Heat from the fire was so intense that steel support girders melted, and part of the highway collapsed eight minutes before the first firefighters even arrived.

I-95 runs from Miami to the Canadian border, and is one of the busiest roads in the U.S. The bridge over Cottman Avenue in Philadelphia served 160,000 or so vehicles each day. There was no doubt the bridge would be replaced, but the question was just how quickly.

A temporary solution opened to traffic just 12 days later—a miraculous feat—but executing the permanent solution was similarly stunning. The new overpass was built in just 30 days.

Most of that heroic work had nothing to do with us. But we will take credit for the protective coating system applied to the bridge’s steel members. It was the same one as at Point-No-Point, just an hour’s drive up the highway. Once again, everyone involved in the project was quite familiar with the system.

Here's why that familiarity made a difference:

- • The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation approved the system in no time because it is NEPCOAT-approved and well-known to their engineers

- • The steel fabricator knows the system very well and its shop painters executed the work flawlessly

- • This being such a common bridge corrosion protection system, we had plenty of product already in stock for rapid delivery to the fabricator

In praise of ordinary

Specifiers and painters today probably regard Carboline’s Carbozinc 11 + Carboguard 893 + Carbothane 133 system as a completely ordinary system to achieve 30 years of maintenance-free bridge steel protection.

No need to dress it up any more than that. Because calling it ordinary is to pay us a high compliment. We’d put that on one of those billboards you might pass on I-95.

The billboard would read: “Ordinary system. Extraordinary peace of mind.”